Thirty Years of Freedom

Making sense of South Africa's trajectory over the first three decades of living with political freedom, via the prism of football.

In May 2024, over two days, I attended a colloquium at the Stellenbosch University Museum on ‘Looking Back to the Future: Living Freedom in the 1990s.” The idea was for the participants, now all in their fifties, to look back over the three decades of South African freedom. The colloquium was organized by the academics Gabeba Baderoon and Louise Green, with about twenty participants. Others invited included Kopano Ratele, Pumla Gqola, Andries Bezuidenhout, Rustum Kozain, Zimitri Erasmus, and Lize Van Robbroeck, among others.

After mulling this over for a while, I finally realized I wanted to structure my ideas around two key events pivotal to postapartheid sports: a photograph taken in mid-1992 and the South African men’s national football team's third-place finish at the African Cup of Nations in Côte d'Ivoire on February 10, 2024.

This is what I wrote:

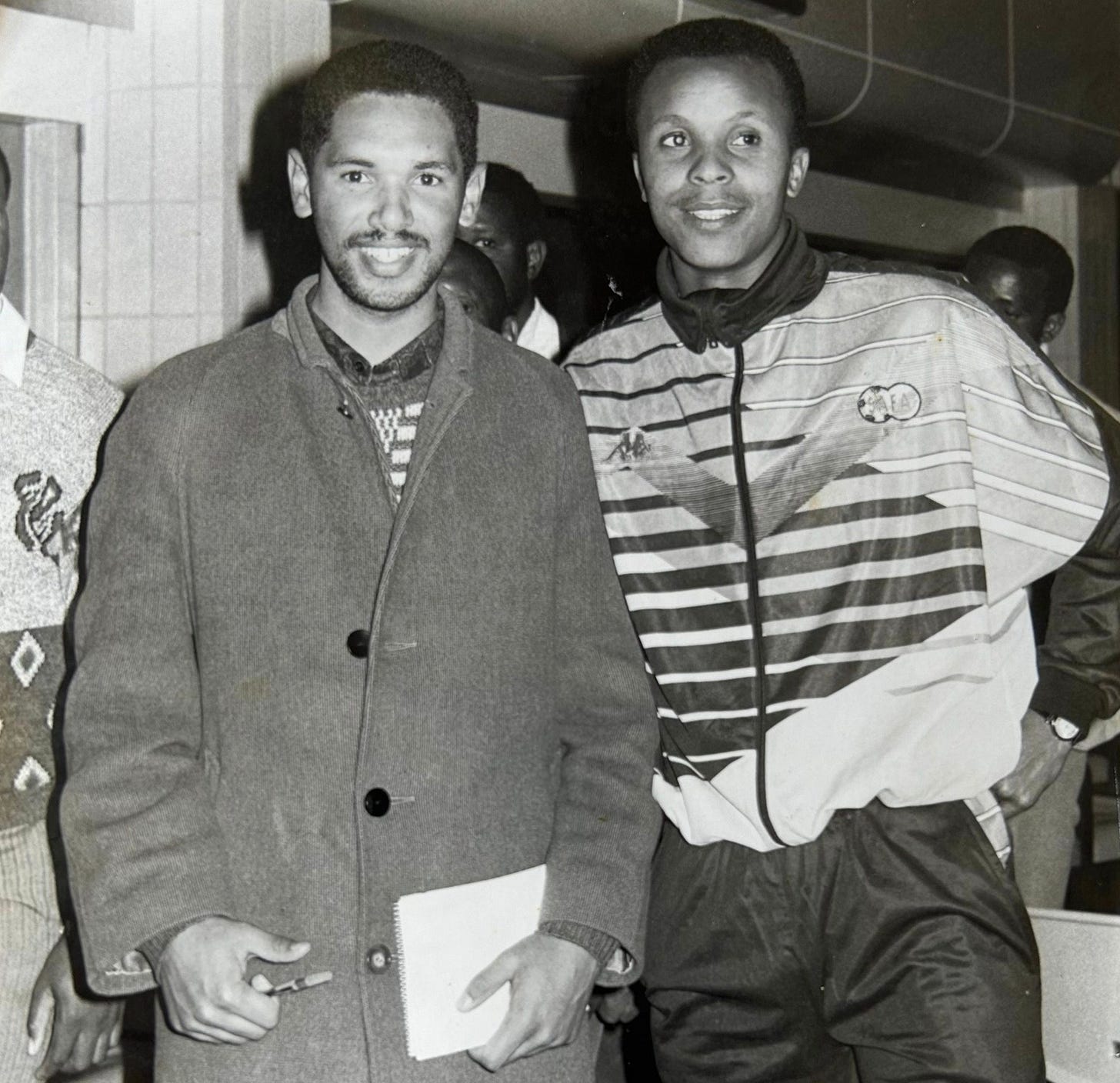

One of my favorite photographs of myself was taken by a journalist acquaintance on July 8, 1992. In the black-and-white print, I am on the left, dressed in a gray overcoat over a mismatched shirt and a striped sweater (what we South Africans call a jersey) and clutching a pen and notebook. Next to me, in a tracksuit, is the footballer Doctor Khumalo. He smiles in a different direction. I look straight into the camera. I was 23, Khumalo 25. We radiate openness and cheer.

We are at Cape Town’s main airport, then named for the troll-like white first prime minister of apartheid South Africa, DF Malan. The sports boycott, which had isolated South Africa from international sport, was newly over.

Khumalo had just arrived with the South African men’s national football team for their match against Cameroon the next day at the Goodwood Showgrounds, north of the city center. The day before, on 7 July, the first integrated South African men’s team had played its inaugural international match, a friendly against Cameroon in Durban. South Africa had won 1-0.

South Africa’s return to international football came after eighteen years of expulsion by FIFA, the body governing global football. When South Africa was drummed out of FIFA in 1976, its national teams in other sports had already been expelled from most international sporting associations. The slogan of the boycotters was “No normal sport in an abnormal society.” Nelson Mandela’s release, the unbanning of liberation movements in 1990, and the ongoing negotiations on a new constitution meant South Africa’s readmission to the global sporting community. FIFA let South Africa back in five days before my picture with Khumalo.

In response to the news, SAFA, the new national association, hastily arranged a three-match tour with Cameroon, Africa’s best team. Featuring forward Roger Milla, Cameroon stunned football giants like Argentina and Colombia at the 1990 World Cup. A desire for confidence influenced South Africa's choice of opponent as they entered the global stage.

History and possibility were thick in the air. However, the occasion reflected the chaos and happenstance of the transition from apartheid to liberal democracy that dominated the early 1990s, including how the Cameroonians' tour materialized at the last minute.

The political transition, often romanticized, was quite violent. Between Mandela’s release and the first democratic elections, local newspapers documented extensive state violence, apartheid death squads, proxy wars against black South Africans, and white right-wing terrorism. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission later found 14,000 deaths and 22,000 injuries from 1990 to 1994. But at the time, none of this dampened the national mood.

Khumalo’s and my posture reflected the potential of what freedom would offer. Khumalo was born in Soweto and played for Kaizer Chiefs, a professional team whose owner–the former footballer Kaizer Motaung– was a representative under apartheid of what would later be called Black Economic Empowerment. By scoring the goal in Durban, Khumalo had made history. As for me, I had grown up poor and working class and had just completed an undergraduate degree in politics at the University of Cape Town. In 1992, I was a general news journalist. The new job came with a scholarship to complete an honors degree in politics.

Khumalo excelled in our national team in the following years, notably fronting South Africa’s attack in its sole African Cup of Nations title run in 1996. His talents took him briefly to Argentina's top league, where he left a lasting impression. Later, he became a prominent figure in the inaugural Major League Soccer season in the United States. As for me, I was awarded a Fulbright Scholarship in 1995 and left South Africa to do a Master’s degree in political science at a university in a suburb of Chicago. When South Africa won the African Cup of Nations, I watched scenes of jubilant fans in Johannesburg streets from my dorm room.

Following the end of apartheid, there was optimism that South Africa, with its history of resistance and progressive Constitution, would undergo a significant domestic transformation and become a beacon of morality on the world stage.

Because South Africa was the final bastion of racial and colonial regimes in the 20th century, its liberation struggle occurred after the global consensus on human rights and non-discrimination had already crystallized. As a result, it was often regarded as an exceptional case. But South Africa soon became an ordinary country.

Globally, certain challenges were unavoidable. The political ideal of nonalignment diminished as newly independent nations grappled with changing geopolitical landscapes. With the collapse of the Soviet bloc, the world saw a consolidation of power, with the United States emerging as the sole superpower, commanding unparalleled military, financial, and economic influence. This era saw the dominance of T.I.N.A. and the Washington Consensus, promoting free markets and trade. Then, there were the demands of financial markets, upon which South Africa heavily relied. The country's economy, dominated by the mining sector, further entrenched these dynamics. The effects were disastrous for South Africa's pursuit of a more equitable growth trajectory.

Inside South Africa, familiar patterns emerged: economic inequality, state corruption (“state capture”), labor rights violations (the low point being the 2012 Marikana massacre), and corporate misconduct (notably the Steinhof bank scandal in which a prominent white businessman was fined for $25.2 million for dodgy accounting). These challenges transcend borders, endemic to democratic societies worldwide.

The late English historian Eric Hobsbawm once wrote about football’s power to clarify how a nation imagined itself and its place in the world: “... The imagined community of millions seems more real as a team of eleven named people.”

The African Cup of Nations victory of 1996 and qualification for the 1998 and 2002 World Cups were soon replaced by what resembled a stasis and downward slide. Except for brief exceptions, like in the African Cup of Nations in Egypt in 2019 when we defeated the hosts in the Round of 16 – the goal scored by Thembinkosi Lorch, a player later accused of violence against his female partner – the team began to reflect the mood of the country: a prolonged depression, not helped by the absence of capable leadership, political will and a lack of national purpose.

After briefly returning to South Africa in the late 1990s to work at a center-left political think tank, I moved to London and then New York City at the beginning of the 2000s. I finished a Ph.D., began an academic career, and started a family.

Back home, social movements hinted at postnational political avenues. Among these were protests on service delivery, land, and privatization, the AIDS movement, and the rise of the Economic Freedom Fighters. The latter emerged in the wake of the Marikana massacre. Its relentless trolling of Jacob Zuma was admirable. But before long, it became clear that it was more a vehicle for Julius Malema's ambitions than a movement of organized people forwarding a grassroots agenda. Similarly, forming independent trade unions like SAFTU suggested that "alliance politics" with the ruling party wasn't the only future for workers. Finally, new student movements underscored systemic issues in their protests and media appearances (when the media covered them). They linked white supremacy, neoliberalism, patriarchy, and nationalism, at times influencing the ANC positively, evidenced by South Africa's expansive welfare state amidst a capitalist economy, a rarity in the developing world. Connected, the AIDS movement’s civil society push compelled the ANC to provide anti-retroviral drugs for HIV patients.

I followed much of this from afar, on television, via streaming services, or the internet. South Africa’s ability and inability to qualify for the African Cup of Nations, held every two years, resembled a time clock determining my mood. Meanwhile, the country’s politics became consumed by the corruption and mendacity of the Zuma years and the turn to the right in its politics, including by Black opposition parties and social movements, as well as in its popular culture.

From mid-January through early February 2024, the men’s African Cup was played in Cote d’Ivoire. South Africa was one of the twenty-four qualifying teams. A few weeks before, the South African government brought a genocide case against Israel to the International Court of Justice in The Hague for its actions in Gaza. Apart from Israel being forced to appear, the court declared that Israel was plausibly engaging in genocide. Beyond the case, the sense was that this action solidified South Africa’s place on the world stage in solidarity with Palestinians and, more broadly, a revived Global South politics. Viewed from within South Africa, it revealed what the government could do if it set its political will and minds to it.

In Cote d’Ivoire, Bafana Bafana faced overwhelming odds. Most African Cup teams rely on European-based stars, while South Africa fielded mostly local players. South African football has failed to tap grassroots talent, akin to economic development challenges. Yet, the squad drew from Mamelodi Sundowns, which had replaced Khumalo’s Kaizer Chiefs atop South Africa's football hierarchy and prioritized developing local talent. Despite expectations, Bafana Bafana clinched third place, admired by its opponents, and on the way to defeating formidable opponents like Morocco, who boasted players from Europe's top clubs. That match carried political weight: Morocco’s players openly supported Palestine, yet their government occupies Sahrawi land, a stance most Moroccans endorse.

When the game ended, a friend WhatsApped: “South Africa defeated occupation twice in one week.”

But these victories—in The Hague or Cote d’Ivoire—are momentary. The end of apartheid and the thirty years since may have erected “normality” as the goal. And that’s certainly a goal that was achieved. But “normality” has proven disappointing in a society needing radical transformation.