The documentary photographer, trade unionist, and public historian Omar Badsha is not really a sports fan. It doesn’t seem that way from the historian Dan Magaziner’s biography, “Available Light: Omar Badsha and the Struggle for Change in South Africa” (Ohio University Press, 2024 and Jacana Press, 2025). The only reference to sports comes early in the book in relation to the fandom of Badsha’s father, Ebrahim, who was himself an artist. Dan writes about Ebrahim Badsha: "He played cricket and enthusiastically supported the neighborhood soccer teams when they played others at Currie's Foundation." The latter was a famous venue for sports and political events organized by Durban’s black and Indian communities.

The image below, by Jurgen Schadeburg, shows fans at a football match at Curries Fountain in 1952. Schaumburg, who was born in Germany, migrated with his mother to South Africa and later worked at the storied Drum Magazine, played a key role in mentoring some of the key figures in black documentary photography (Ernest Cole, Peter Magubane, Ranjit Kally) who would influence Omar’s own photographic practice.

I wanted to ensure I was right about Omar, sports and sports photography, so I checked with Dan, who confirmed that Omar wasn’t a sports fan: “Or at least, it doesn’t come up.”

In 1995, Omar was invited to exhibit his work in Denmark. During that visit, he created some sports-themed works, including a portrait of a football player and pitches in and around Denmark.

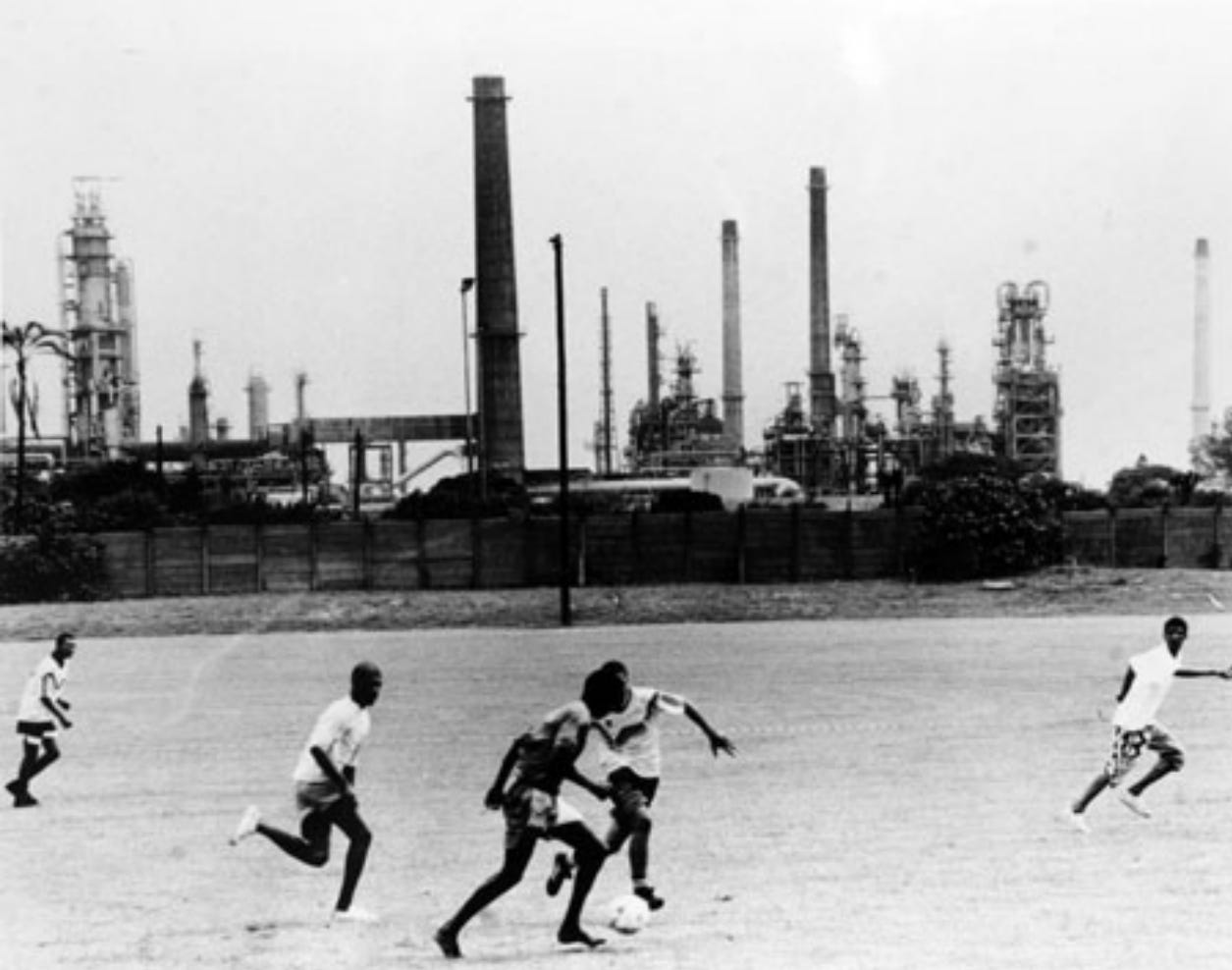

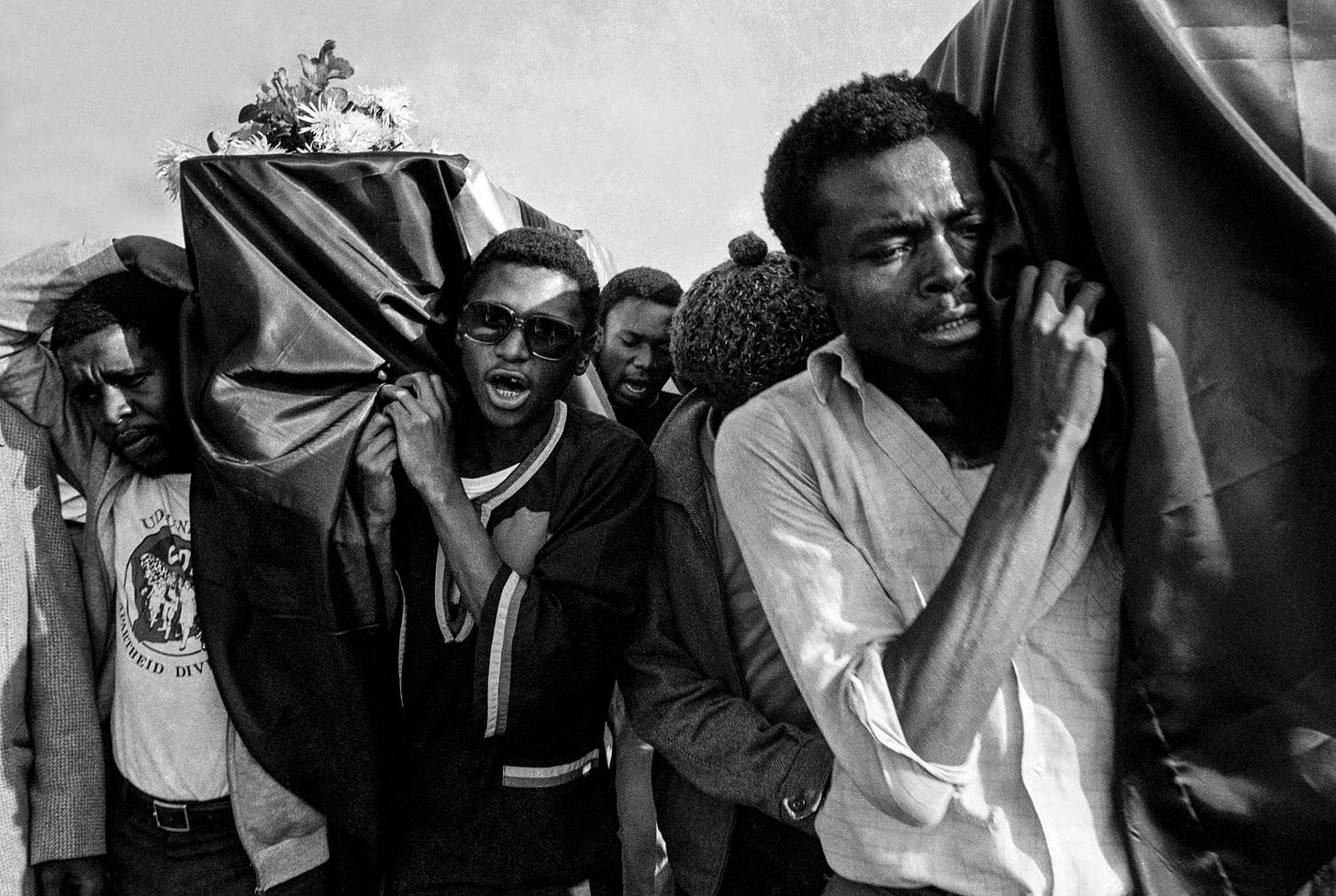

Badsha is perhaps best known as a co-founder of the Afrapix Photo Collective in 1982, a group of primarily Black photographers (with some white members) who used their photography as a form of activism. From my limited understanding of Afrapix’s history, I know that some of its founding members, particularly Cedric Nunn and later Peter McKenzie, photographed sports—especially football—though this work was produced mainly after the end of apartheid. For instance, McKenzie was involved in several photography projects tied to the build-up of South Africa’s 2010 World Cup, and Nunn created some sports-related images, particularly in the post-1994 era. I’m pretty sure I’ve seen sports-themed photographs in Nunn’s “Blood Relatives” series, which he began in the 1980s, a project about his family in KwaZulu-Natal. One striking example is his photograph of footballers, in 1995, playing a match in Wentworth, a coloured township in Durban, located near an oil refinery, which adds a layer of environmental and social commentary to the scene.

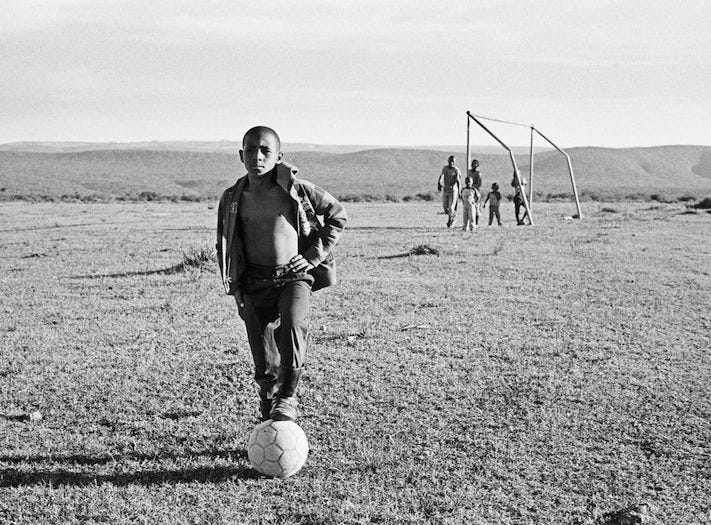

Another comes from Nunn’s project, “Unsettled: One Hundred Years War of Resistance by Xhosa Against Boer and British.” This photograph is entitled: “Looking out towards Grahamstown, KwanNdlambe Village, Peddle, 2012”

In any case, back to Omar, at the end of October 2024, I was invited, along with literary scholar Sarah Nuttall of Wits University, to make some remarks about “Available Light” at an online seminar about the book for Carleton University's “Knowing Africa” (online) Seminar Series on October 30, 2024. The South African political scientist Shireen Hassim organizes the series. Below is an edited and expanded version of my comments, which I have adapted for this Substack.

Omar never learned to use a flash and works exclusively with available light. His approach to photography mirrored his broader approach to life and politics—a “counter-telos,” as Dan puts it. Born in 1945, Omar “justifies his life not in reference to sacred texts or religious leaders, but to ideological foundations—socialism, nonracialism, humanism, democracy—and secular mentors, all of which he often groups under the broad tent of the ‘struggle,’” the term used in South Africa for the long resistance movement against colonialism and apartheid.

Dan’s book offers a deep, sympathetic account of Omar, once described by African-American academic and writer Tiffany Willoughby-Herard as “a giant of South African documentary photography.” Omar worked as a trade unionist, photographer, and, after the end of apartheid, as an online archivist.

Born into a working-class Indian Muslim family with personal ties to the struggle, his adult life intersected with key moments in South Africa’s resistance history between 1970 and 1990. His notable photobooks include the iconic “Letter to Farzanah” (1979), “Imijondolo” (1985), and “South Africa: The Cordoned Heart” (1986). In the post-apartheid period, Omar became a public historian by founding and building the SA History Online portal.

Omar may not be a household name despite his role in several major political currents from the late 1960s through the early 1990s. As Dan notes, Omar was “a participant more frequently than he was someone who shaped events,” and he was “a particular sort of participant.” His obsession with collecting, cataloging, and archiving objects from his life is central to Dan’s narrative. The Badsha family, three generations removed from their Indian roots, migrated to South Africa as economic migrants.

Omar’s early life, marked by racial violence, his mother’s mental illness, his father’s temper, and the challenges of dyslexia, shaped his later engagement in politics. Whether in the trade union movement of the 1970s, identifying as black while keeping the Black Consciousness Movement at bay, or the nonracial politics of the 1980s, politics provided Omar with a form of therapy.

Since 1994, nearly a thousand biographies of prominent South Africans have been published. However, Dan argues that Omar’s life merits attention “because it is in the ephemera of his ‘ordinary’ South African life that we can see how activism was born at the intersection of desire and need, in the lives of those who maintained it.” Dan candidly discusses the challenges of writing about a living subject. His reservations aside, I was struck by the book’s engaging pace, superb writing, tight storytelling, and exceptional attention to detail. Dan’s ability to capture so much history and nuances of people and events in just over 230 pages is truly impressive.

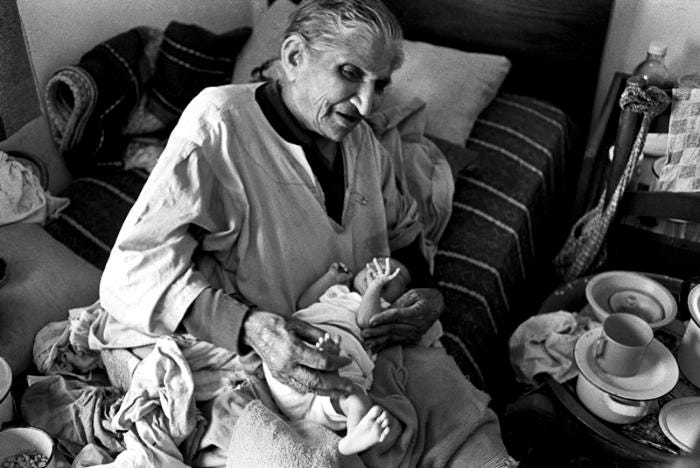

Many familiar figures and organizations from South Africa’s collective history, notably from the black majority, many now largely forgotten, appear throughout the book: A.K.M. Docrat, Harry Gwala (who I had the privilege of seeing in action in person), Mewa Ramgobin, Albertina Sisulu, Nokukhanya Luthuli, David Hemson, Rick Turner, Strini Moodley, John Gomas, APDUSA, the Chemical Workers Industrial Union, the photography collective Afrapix (which Omar founded), and the Second Carnegie Project (which spawned “South Africa: The Cordoned Heart”) and the ANC’s cultural desk (with whom Omar would develop artistic and political differences, like with Afrapix, after 1990) to name just a few. With Omar’s assistance, Dan brings figures like Gomas—whom Omar photographed in District Six, Cape Town, in 1978—to life. Gomas, born in 1901, was one of the first Black (including Coloured) members of the Communist Party of South Africa. In one of the book’s striking moments, Dan describes a visit Omar made to Gomas’ home, where he sat debilitated by a series of strokes, reading a newspaper by a light that streamed through his window. With his halo of white hair glowing, Gomas seemed “like a figure out of time.” He passed away soon after, and the government demolished his house and those of his neighbors shortly thereafter.

Dan has done significant work shedding light on the lives of Black artists and intellectuals under apartheid. His first book focused on the genesis of the Black Consciousness Movement, and his second explored Black artists and teachers working in Bantu education schools from the late 1950s onwards. Studying Omar’s life synthesizes the themes explored in Dan’s previous works: art and commitment, meaning-making, and self-making, all within the context of the struggle for change in South Africa’s past and the battle over history in South Africa’s present.

This book also contributes to the growing body of urban histories that usually explore cities like Cape Town and Johannesburg, especially the erased cosmopolitan spaces of District Six and Sophiatown. “Available Light” puts Durban and urban KwaZulu-Natal at the forefront—not only focusing on the social world of “the Durban moment” (the 1973 worker strikes or the beginnings of the Black Consciousness Movement) but also emphasizing the city as a space where Zulu and Indian South Africans crafted a unique variant of South African culture. Central Durban, where Gujarati Muslim Indian South African families like Omar’s lived and made meaning alongside descendants of indentured laborers and “passenger” Indians, is at the heart of the book.

Omar’s work – including his photography – and his politics emphasize building solidarity among Black groups, particularly between South African Indians and Black Africans. Notably, Omar’s first conscious memory is of the January 1949 pogroms in Durban, when Africans and Indians engaged in retaliatory violence. Omar, only three years old at the time, witnessed this pivotal moment in South Africa’s history. It would mark him for life. This theme of solidarity runs through the book, reflecting Omar’s many friendships and comradeships with figures as diverse as artist Dumile Feni (his earliest closest friend who stayed with the Badshas for prolonged periods in the 1960s), poet Mafika Gwala and lawyer Mafika Mbuli, among others.

The book does not shy away from addressing the racial politics of the left during the struggle and delves into his complex relationships with prominent white leftists. Dan describes how several prominent white figures—whether in the art world, journalism, or the trade unions—found Omar difficult. The white photographer David Goldblatt, who stood in as a representative for documentary photography and who funded and admired some of Omar’s work, had a strained view of Omar, even calling him a “dogmatic” and “a Marxist sort of Communist.”

Omar shrugged off Goldblatt’s criticisms. “In South Africa,” Dan writes, “Goldblatts no longer lived in the ghetto Badshas did. For all the talk of nonracialism and organizations that were like families, there was no alchemy to remove race from these interactions. Since first he had entered the art world, Omar had had to deal with whites with their own agendas, in which people like himself were bit players at best, or objects to be manipulated at worst … it took quite a leap of faith to think that it was not true with those whites who professed total commitment, while holding onto their passports and access to the comforts that white skins could sometimes afford.”

While tense at times, the relationship between Omar and Goldblatt also featured deep respect and mutual admiration. Goldblatt’s later support of Omar’s projects was crucial, even though they often clashed over political approaches, particularly regarding the role of apartheid’s racial capitalism and Goldblatt’s willingness to have his work sponsored by mining corporations.

“Available Light” is also a revisionist history of documentary photography in South Africa. It begins with figures like Ernest Cole, Ranjit Kally, and Peter Magubane, who represent the photographic traditions that Omar engaged with first. (Omar would meet Cole in 1990, right before the latter died in New York City. Omar had received his first passport then and traveled to Denmark and the US.)

Omar’s first significant influence as a photographer was his father’s brother, Moosa, who worked as a freelance photographer in Durban and was an acquaintance of Ranjit Kally, the famed “Drum” magazine photographer.

I couldn’t help but draw connections between “Available Light” and Mahmood Mamdani’s 2020 book, “Neither Settlers Nor Natives: The Making and Unmaking of Permanent Minorities.” South Africa is one of Mamdani’s case studies. Mamdani examines the political turn of the 1970s, when the Black Consciousness Movement redefined blackness as a political identity, influencing broader left politics in the 1980s. This revisionist reading of South African history seems to resonate with the life and political journey of someone like Omar—an ordinary South African whose struggles and triumphs offer insights into broader social movements.

On a personal note, I’ve admired Omar for years and am proud to call him a friend. I first became aware of his work while studying at the University of Cape Town between 1988 and 1990, when “The Cordoned Heart” was published. Omar’s associations include his work at the South African Development and Labour Research Unit (SALDRU) and the Center for Documentary Photography, part of the Center for African Studies (described by Dan as a “poorly funded backwater in a very slowly transforming and still very Anglocentric institution”). Omar’s wife, Nasima, ran the Academic Support Program (ASP), which many of my friends utilized. (Nasima is a political figure in her own right, deserving of a biography.) As I read about the late 1980s in “Available Light,” I was surprised to learn that our paths didn’t cross then. I was in my late teens, and much was happening at UCT. In the early 2000s, right after I had moved to the US, I became friends with Omar’s daughter, Farzanah, which is how I came to know Omar personally. I would check in on him in Cape Town, and he stayed with us in Brooklyn when he later came on his second US tour.

This book holds a special meaning for me because I understand the tremendous effort it took for someone like Omar to break free from the constraints of apartheid. He is of my parents’ generation, and I’ve seen how apartheid restricted their potential. Omar’s ability to carve out the life he did is a testament to his resilience and his many talents.