Automatic Withdrawal

The latest in my occasional series on the connection between sports, mostly football, and politics.

• Last week, Dynamos Basketball Club from Burundi was disqualified ("removed;" "automatic withdrawal") from the latest round of the Basketball Africa League or BAL, being played in South Africa, for partially taping over the ‘Visit Rwanda’ logo on their jerseys. Rwanda’s Tourism Board is the league's main sponsor. The players covered the logo in protest against Rwanda's alleged involvement in the war in the DRC and for aiding rebels in Burundi. Dynamo was forced to forfeit two games against Fath Union Sport from Morocco and Petro de Luanda from Angola for refusing to uncover the logo.

The BAL was created by the NBA in partnership with FIBA, which globally governs basketball. The BAL is “a Champions League-style competition for African club teams" (per the AP).

The "Visit Rwanda" logo appears on the Arsenal, Bayern Munich, and Paris Saint-Germain uniforms. Related, the BBC reported last month that a Rwandan club, Rayon Sports, announced that it"parted ways" with a Congolese player at the club, Heritier Luvumbu, after he had "cover(ed) his mouth with his left hand while pointing his fingers to his temple, mimicking a gun, after scoring from a free-kick" in a league game. Luvumba was imitating a gesture made by the DR Congo national team before the start of their Afcon semi-final against Cote d’Ivoire, also in February. Two days later, the Rwandan FA suspended Luvumbu for six months because it "prohibits the use of political symbols or words in football."

• Speaking of Rwanda. When Pele was alive, he was always followed by questions that he tolerated and even shilled for Brazil’s dictatorship in the 1960s. The truth was more complicated. In the

documentary about his life, a then-very old Pele talks about the political pressure he was under from the military dictatorship — in power since 1964 — for him to play in the 1970 World Cup and that they demanded victory and nothing less. Now, two years after he is no more, Pele has a stadium named after him in a dictatorship, with the blessing of FIFA president Gianni Infantino.• Meanwhile, in Portugal, a far-right party led by a former football pundit famed for his racism and xenophobia may be the kingmaker in forming a new government following on March 10th. Andre Ventura's Chega (Enough) - which is ideologically aligned to Geert Wilders and Matteo Salvini's parties - singles out minorities, especially Portugal's small Roma community, for "crime, squatting and exploiting Portugal's social welfare system." As the @Guardian reports, the incumbent Socialists were tied with the center-right coalition, which will most likely form a new government. But the latter may need Chega to get them over the line. According to the Financial Times, as a TV football pundit, Ventura's schtick was to present himself as "a fanatical supporter of Lisbon club

." What much of “fan TV” feels like these days.In 2020, during COVID-19, Ventura proposed quarantining Portugal’s gypsy community to fight the spread of COVID-19. The great Ricardo Quaresma (a star at Sporting, Porto and Beşiktaş; and 80 caps for Portugal) commented (translation via

on Twitter): “I am a gypsy, just like the other gypsies. The racist populism of Ventura serves to turn men against other men.”• I plan to get a copy of Nicholas Blincoe’s “More Noble Than War: A Football History of Israel-Palestine.” (The latter link is to a podcast interview about the book with

).• Related, per

: Beautiful film by my friend Saleh Barahmeh (of on football and resistance in Morocco: Its government may have “normalized” ties with Israel, but the people stand with Palestine — and no regime can control what happens in a football stadium:• Throwback: Ashley Forbes was a prominent anti-apartheid activist in Cape Town. He had become radicalized at his coloured high school in the early 1980s and had joined the United Democratic Front, formed in 1983 to oppose government “reforms” to coopt moderate Blacks (Africans, coloureds, and Indians) and thereby prolong apartheid. The reforms were widely rejected. Incidentally, that was my first year of high school, so I remember it well. But, back to Forbes. At the University of the Western Cape, where he studied physical education, Forbes came into contact with underground African National Congress structures and joined its armed wing, uMkhonto weSizwe (MK). For most people, MK now means Jacob Zuma’s corrupt political party, but it had a history before this. Following military training in Angola, Forbes returned to South Africa, but shortly after arrested, tortured, held in solitary confinement, and then tried and sentenced to 15 years by an apartheid judge in 1987. Which is how he ended up on Robben Island, off the Cape Town coast. The point of this tweet is a story Forbes told in a post, written during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic and widely available online, about his first moments arriving on Robben Island. This is perhaps my favorite part: ‘... When I first set foot in B-Section, with the warder banging the iron door behind me, I see a solitary figure coming up the passage to meet me. He looks me square in the eye and asks, “Chiefs or Pirates?” I say, “Pirates”, and for a moment I can’t read anything in his expression. He smiles, puts his arm around my shoulder, introduces himself as Peter Paul Ngwenya and walks me down the passage to introduce me to the comrades. He tells everyone that I support Pirates, the Buccaneers who “work hard, win easy”.’

The images below are of Forbes and Ngwenya later in life. Both Forbes and Ngwenya were released in February 1991, shortly after the apartheid government unbanned the ANC and announced it would release all political prisoners. Football, of course, was key to the survival of Robben Island prisoners.

The historian Peter Alegi (Michigan State University) messaged me that Ngwenya worked in the prison kitchen and of Ashley Forbes’ testimony before the country’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission in the late 1990s of being brutally tortured.

• The South African sociologist Eddie Webster died on 5 March 2024. Webster, known on X as @sociologymadala, was a professor at the Southern Center for Inequality Studies at Wits University in Johannesburg. More than that, he was a prodigious researcher and activist on labor and trade union issues, including well into his old age. Among others, he helped revive the black trade union movement in South Africa, was active in resistance politics, and, after apartheid, taught many trade unionists at the Global Labor University. In 2021, the HSRC’s Gregory Houston appraised Webster’s long academic career: Webster was "credited with influencing several generations of sociology students at Wits, transforming the sociology curriculum at the university, and producing a new generation of black sociologists."

In a post on Africa Is a Country, Webster’s friend and fellow sociologist Michael Burawoy (they first met in Johannesburg in 1968) wrote about Webster’s remarkable life. It included this vignette: "One of the late Eddie Webster's earliest protests occurred when he was president of the Rhodes Student Representative Council (SRC)—the demand to lift the ban that prevented Africans from watching university rugby. As he writes, in a self-critical vein, “We were protesting on behalf of black supporters to watch our rugby not for non-racial rugby teams or the right of all players to participate in the same league.”

On Facebook, the sociologist (he was colleagues with Webster at Wits) and trade unionist (in the US), Glenn Adler commented on my post: “Self-critical, on Eddie’s part, indeed, and told with a chuckle to mark his awareness of how far he’d moved in the intervening years. At the time he and his fellow protesters weren’t aware that blacks actually played rugby (in the heart of the Eastern Cape!) and sang We Shall Overcome while demanding ‘open admissions’ to the university’s rugby ground.”

In the image below, of the very white 1965 Rhodes University SRC (source: Flickr, Rhodes University Archive), Webster is in the front in the middle.

• The music culture site Passion of the Weiss West has a new “Set Piece” column by

The main reason to come back for the column will be if he keeps writing entries like the last part of the latest one: that section on '“Carnival,” Kanye & the Curva Nord Milano,” which breaks down the American musician’s sampling of chants by the club’s rightwing fanbase in a new song. That is enough to recommend the Set Piece column.• On Tuesday, March 5th, I joined

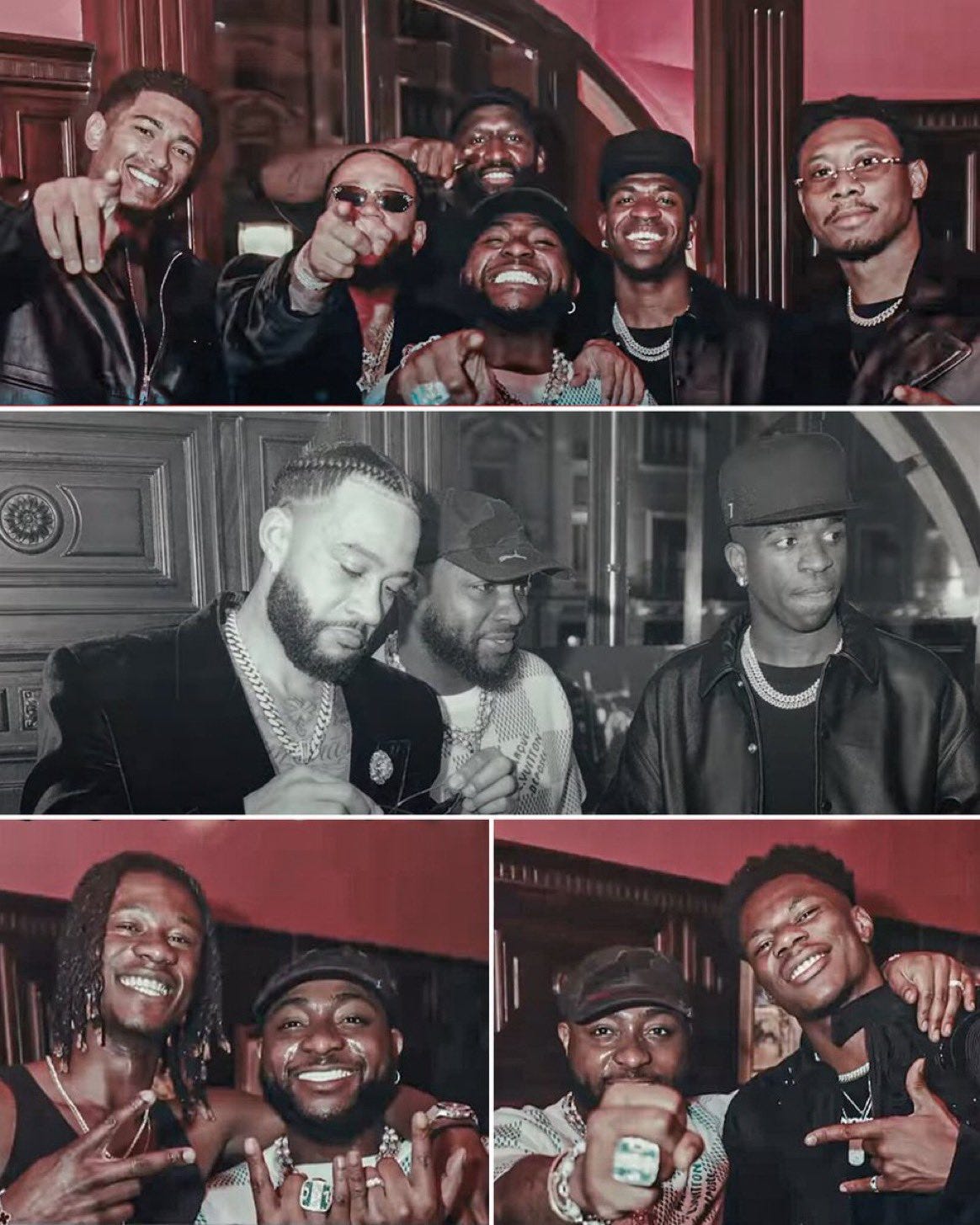

, Africa Is a Country’s football correspondent and the producer of the weekly football podcast , for a panel discussion hosted by The Africa Center in New York City for a post-Afcon discussion on the state of African football post-Afcon. The Ghanaian writer Fiifi Anaman was to join us, but technical difficulties prevented him. Tunde Olatunji of the Africa Center moderated the panel. I am clean-shaven (the result of a snafu trimming my beard) and stare confusingly up at the ceiling (it’s the computer camera angle) and I brought the Nigeria social media jokes. Maher, though, was very professional. You can re-watch the panel here.• Is this the new pan-Africanism? Black footballers Jude Bellingham, Vinicius Junior, David Alaba, Antonio Rudiger, Eduardo Camavinga, Aurelien Tchouameni, and Memphis Depay—all, except Depay, play for Spain’s blackest football club, Real Madrid—feature (about the 1:30 mark) in Nigerian Afrobeat singer Davido's latest music video for his song "Away." I bet they were looking for a break from the all-out assault of Spanish fan racism.

• It would be wonderful if this film, "Larbi, Justo… et les autres," were available on streaming services and with English subtitles. Part of a TV documentary series, “Histoires et des Hommes,” and made for Moroccan channel 2M before the 34th African Cup of Nations in Cote d’Ivoire (where Morocco crashed out against South Africa in the Round of 16), the film explores one hundred years of Moroccan football, including of Hassan Akesbi, Abderrahman Belmahjoub, Larbi Benbarek (“the Black Pearl”) and Just Fontaine (who scored 13 goals for France in the 1958 World Cup; still a record).

• Finally, I’ve been scouring the London Review of Books archives, looking for what the magazine’s contributors wrote about football. My favorites from the first decade — the LRB first published in October 1979 — comes from novelist Martin Amis in 1981: “Readers of the London Review of Books who like football probably like football so much that, having begun the present article, they will be obliged to finish it …” The best insight comes from John Lanchester in 1989: “... One of the mysteries about football is the depth of the need it seems to fill. It’s as if the conditions of modern society help to create people who have inside them a football-shaped hole. Hardly anything ever written about this phenomenon ... gives any useful insight.”